Porpentin e is a video game designer and writer, better known as a developer of hypertext games made with Twine. In her website, she describes herself as “a fem organism in oakland who makes everything“. In this article I am going to briefly describe four of the works that comprise “Eczema Angel Orifice“, a compilation of twenty five of her works

e is a video game designer and writer, better known as a developer of hypertext games made with Twine. In her website, she describes herself as “a fem organism in oakland who makes everything“. In this article I am going to briefly describe four of the works that comprise “Eczema Angel Orifice“, a compilation of twenty five of her works

Porpentine is one of the most interesting and intensely innovative hypertext fiction writers there are. Imagine the surreal nightmarish worlds of David Lynch, the strange cities of Italo Calvino, the bleakness of Samuel Beckett in a work of interactive fiction. And after all that name-throwing and reference-juggling you won’t be even close to really describe what Porpentine is and does.

You would be leaving out the themes and the emotional landscape of Porpentine’s work. The fear of being alone. The ritualistic nature of work. The inherent violence of the cities. There is something very dark, very bleak in her works, but sometimes, in the middle of that, you can find real beauty, real hope, and a real hunger for life.

You would be leaving out the themes and the emotional landscape of Porpentine’s work. The fear of being alone. The ritualistic nature of work. The inherent violence of the cities. There is something very dark, very bleak in her works, but sometimes, in the middle of that, you can find real beauty, real hope, and a real hunger for life.

And after all this introduction, I still feel I haven’t said anything about her works that could give you an idea of what you can expect from them. They are not for everyone, nor for every mood. But if they are experienced at the right moment and with the right set of mind, they reveal themselves as one of the most powerful and beautiful experiences you can get from interactive fiction.

Just give them a go. Trust me, they are really worth it.

With nothing else to add, I will start with the games themselves.

Begscape

Begscape is a very simple game. You are a wanderer, going from one strange city to another. The names and descriptions are randomized, but they are all strangely evocative (“Mursdi is a citadel of ebony bricks and crimson thatch. There are many smokehouses and gambling parlors.“) hinting at a deeper story.

What do you do in those cities? Beg. Just beg, for food and shelter. If you don’t manage to get enough money to survive, you get more and more ill until you die. You can try your luck at another city, but eventually the ending is always the same. You try to survive, you don’t get enough money, you die.

It’s just a short poem, simple but sharp. The contrast between a strange, fantastic world, and the futility of your existence. So many things to discover, but so little things to do when you are powerless, and always death at the end of the way.

With Those We Love Alive

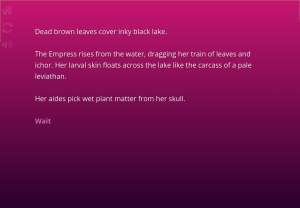

You are at the service of a monstrous Empress in a strange world, where everything that happens is dark and disturbing, but everyone (even the protagonist) is used to it. In this game, you are tasked with crafting weapons and symbols for the empress, but you can also spend your time exploring the palace and the city beyond.

You are at the service of a monstrous Empress in a strange world, where everything that happens is dark and disturbing, but everyone (even the protagonist) is used to it. In this game, you are tasked with crafting weapons and symbols for the empress, but you can also spend your time exploring the palace and the city beyond.

Eventually, you discover there’s no use to it. The people in the city are broken and defeated. You explore the canal, the palace gardens, the mysterious temples and streets. Yet, soon there is no more to see, and you finally begin to repeat the same routine time after time, waiting for something to happen.

And it happens. At some points, the world reveals its cruelest and most violent nature. At other points, you find hope. Hope of being loved, hope of becoming what you want to be.

It is a powerful experience (though not exactly a game by any means). And it is the only interactive fiction I know that entices us to write on our skin at several points.

Ultra Business Tycoon III

This would be the closest thing to a game I’ve played from Porpentine. Become a corporate executive in a nightmarish world born from a nightmare of Samuel Beckett and the simulation games from the 80s. The aesthetic of this work tries to hint at those ugly old 8-bit simulators, with their bright colors and their shareware codes.

This would be the closest thing to a game I’ve played from Porpentine. Become a corporate executive in a nightmarish world born from a nightmare of Samuel Beckett and the simulation games from the 80s. The aesthetic of this work tries to hint at those ugly old 8-bit simulators, with their bright colors and their shareware codes.

There are puzzles in here, and some of them are very good (my personal favourite is the one related to the difficulty setting). But the best of it is the description of the world, a satire of capitalism and cyberpunk sci-fi. Ugly and gruesomly exaggerated. Our objective in the game is to win one million dollars, in order to pass “The Mammon Gates”, a place “where glory, fame and power awaits”.

And yet there is another story, gradually hinted at, through several passages in italics. Another character, a boy who spends his time playing this computer game in order to forget about the mess that his own life has become. By the time we reach the end, that secondary story becomes the most important one; the story of Porpentine herself.

The last passage in this game is a beautiful and powerful message.

Skulljhabit

This game repeats one of Porpentine’s main themes: Work and routine. Life as an exercise of futility.

This game repeats one of Porpentine’s main themes: Work and routine. Life as an exercise of futility.

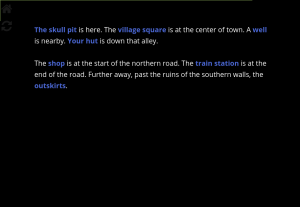

We have been assigned by a mysterious company a position in Skull Village. Our work? To shovel skulls endlessly in a place called “the skull pit”. It is a pointless work, but as Porpentine says, “all work is ultimately pointless under capitalism: self-perpetuating and ritualistic“.

There are other things we can do, of course. We can find out more about the local lore of the village. We can visit the mountain and the caves, and discover hidden and mysterious places.

But at the end? “No matter how entracing the world around you is, no matter what secrets it hints at, you must go wherever they tell you, uprooted from your personal goals“. You end up being “promoted” to have another boring job in another city. You end up repeating time after time the same routine, the same mantra. All those strange places, those stories only hinted at, will never be fully revealed.

And that’s the end of it.